Menu

Menu

Menu

Menu

Everyone should consult their health care provider to determine what medical procedures are best for them. That understood, the overwhelming consensus of the medical community is that for most people, vaccines are safe and effective.

Nonetheless, sensational, outlier events do happen. These events tend to stick in our minds and tug at our hearts. They evoke our sympathy, play to our fears, and compel us to demand better. This is especially true in the age of social media, where a single story can be amplified like never before.

A single story or event—no matter how compelling—cannot always be taken as a wholesale reflection of our collective reality. Over the past 70 or so years, about once every generation a widely-discussed event has cast doubt on vaccines. Consider how these events have shaped public perceptions, and influenced our behaviour.

Perhaps the greatest modern vaccination failure came in the first year of mass polio vaccinations. A faulty batch of vaccine was produced by Cutter Laboratories. 120,000 doses were given that contained live polio virus, instead of weakened virus. 40,000 children developed polio: most cases were mild, but over 160 children became paralysed and 10 died.

The tragedy spawned even more stringent government regulation of vaccines, building on a process that began in the early 1900s. It also opened up vaccine manufacturers in the United States to a flood of lawsuits. Courts ruled that Cutter Laboratories was liable to pay compensation to the people harmed by its faulty vaccine.

Fortunately, the vaccine drive continued without major problems. By 1962, 400 million polio vaccines were safely given, virtually obliterating the disease in many countries.

Every medical procedure requires us to put our trust in others. What does society lose if we lose our sense of mutual trust?

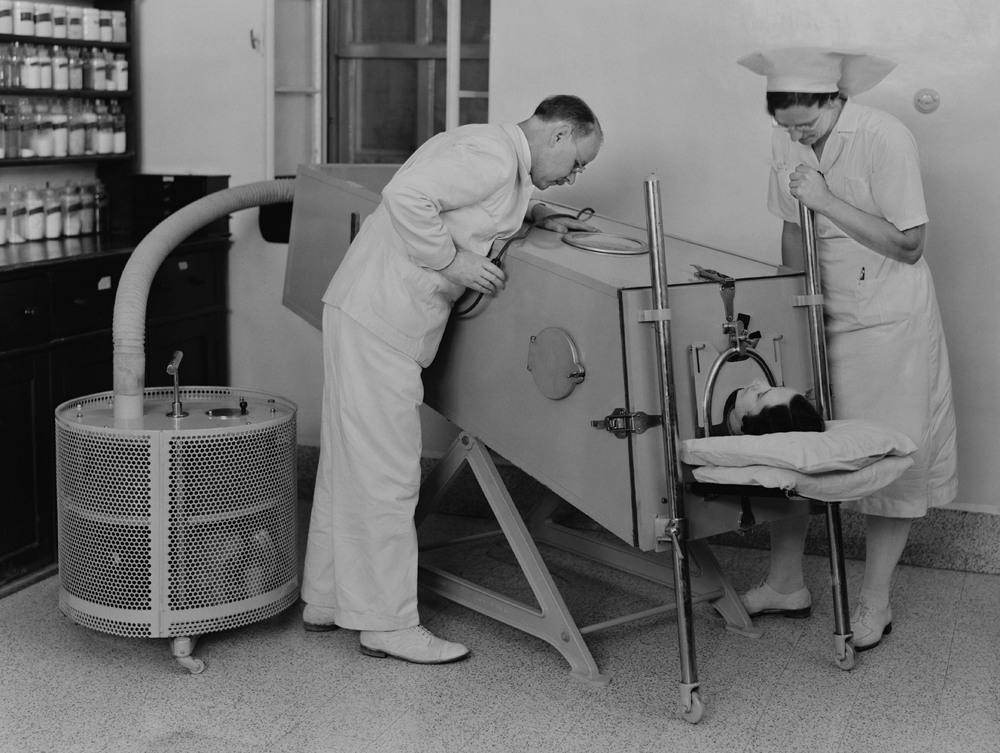

Some polio patients became so weak, they needed iron lungs to breathe. Such scenes reinforce why many Americans feared polio almost as much as the atomic bomb.

When a new strain of swine flu broke out, the American government feared the worst. Thus, a mass vaccination campaign was planned.

The campaign was delayed when vaccine laboratories announced that although the vaccine appeared to be safe, they could not secure liability insurance for their vaccines. This was partly a result of the litigious nature of Americans: precedents had been set by polio vaccine lawsuits in the 1950s. The announcement rattled public confidence. As the Center for Disease Control’s director later said, a message was sent that “There’s something wrong with this vaccine.”

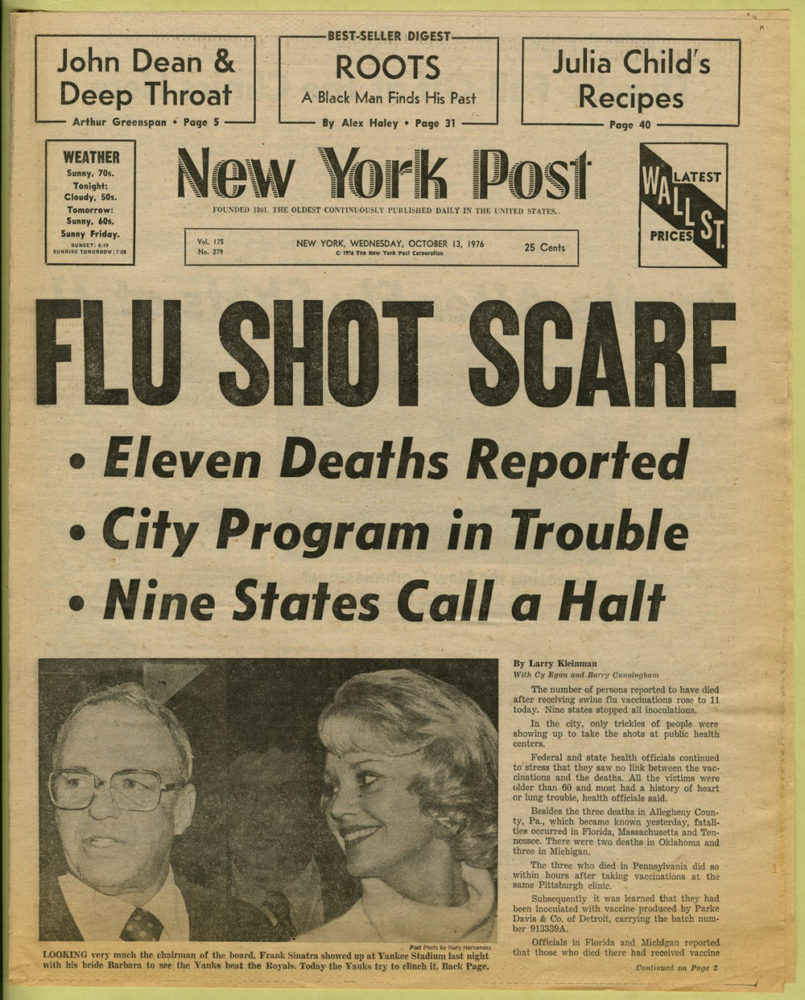

Nothing unusual happened, medically speaking, from the vaccinations. However, the rocky start led to the media amplifying unsubstantiated claims about the vaccine. One New York Post headline panicked about vaccinations at a “Pennsylvania Death Clinic” when three Pittsburgh seniors died of heart attacks almost certainly unrelated to the vaccine. The flu ultimately turned out to be mild, and the vaccination campaign was disbanded.

Are some media sources more responsible than others? What factors give you trust in what you watch, read, or hear?

New York Post, October 13, 1976. Stories about vaccine fatalities became so outrageous, there was even speculation that a mob boss was murdered with a vaccine.

In the 1990s, a belief took root that vaccines caused autism. The belief was cemented in by an infamous report published in the medical journal The Lancet. British doctor Andrew Wakefield, along with a dozen co-authors, suggested that there may be a connection between vaccines and autism. Even though the report cautioned that more research was needed, the claim caught fire in anti-vaccine circles.

When people looked more deeply into the report, it came into serious question. First, several researchers were unable to replicate the study’s findings. Second, it was discovered that some key data was manipulated. Third, it was revealed that Wakefield received more than £400,000 from American lawyers trying to connect autism to vaccines, for a lawsuit against pharmaceutical companies.

In 2010, The Lancet retracted the report and Wakefield’s medical licence was revoked. For his part, Wakefield denies that he misrepresented facts or acted unethically. He remains active in anti-vaccination movements. To date, no lawsuit blaming autism on vaccines has been successful.

How much stock should we put in a single scientific study, especially if its findings are preliminary or speculative?