Menu

Menu

Menu

Menu

A word can have more than one meaning. To know what we mean in any particular situation, we need to define our terms.

“Fake news” means a lot of things. Fun satirical news programs have been called fake news. Websites that publish malicious and misleading reports have been called fake news. Even reputable news organisations have been called fake news.

With so many uses for the words fake news, what can we make of its meaning? A good place to start is the Oxford English Dictionary. OED defines fake news as “news that conveys or incorporates false, fabricated, or deliberately misleading information.”

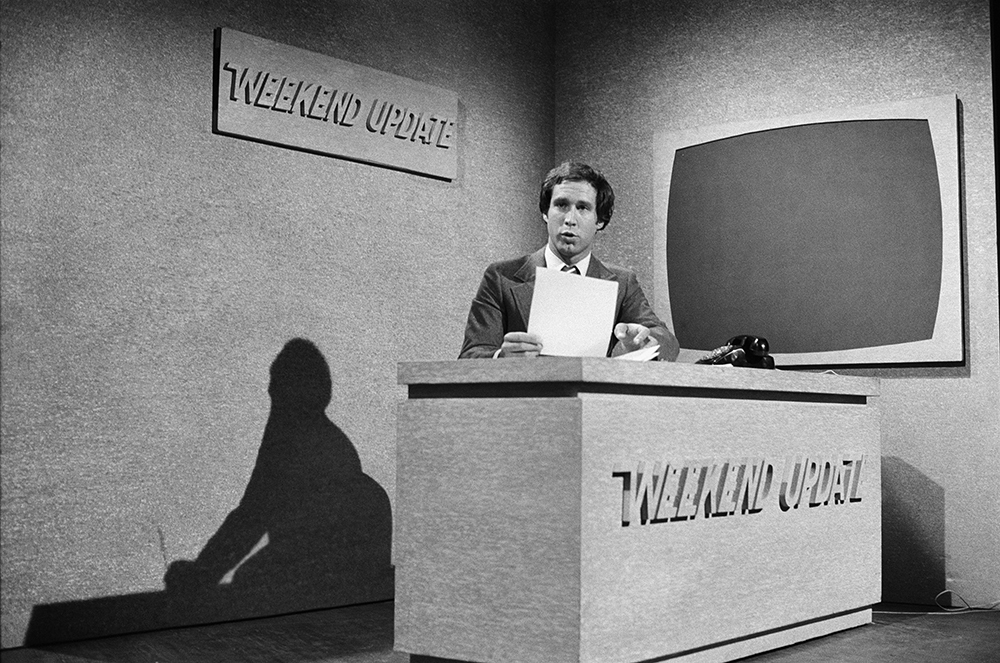

Saturday Night Live’s Weekend Update began in 1975, created and hosted by Chevy Chase. Though not the first fake newscast, it popularised the format.

News full of false, fabricated, or deliberately misleading information is nothing new. Across history people have used fake news to cast doubt on their rivals, build support for the causes they believe in, or just to have fun. Take the civil war in Rome some 2000 years ago. Emperor Octavian created poems that spread lies about his rival Mark Antony. As well, Octavian minted coins that glorified and at times stretched the truth about himself. In other words, Octavian was peddling fake news.

As technology evolved, fake news followed suit. The printing press, invented in 1440, was a key advance in how we spread ideas. For the first time, people could print countless copies of pamphlets filled with all sorts of news and information.

Historians such as Elizabeth Eisenstein say that this newfound ability to quickly print information and spread it far-and-wide was the single-biggest factor in the breakdown of the Catholic Church’s domination over Europe. However, not every pamphlet was fair or accurate. False and inflammatory publications—that is, fake news—heated tempers and helped spark religious wars.

The next key advance in fake news came in the 1800s, once newspapers became established sources of information. Unsavoury newspaper publishers would print fantastical or outrightly false news to increase readership or spread propaganda. Readers of the day called out this practice for exactly what it was: fake news. The words were widely used by 1890, the year the Oxford English Dictionary marks as their entry into the English language.

The term fake news didn’t remain in common use for long. In the early 1900s the newspaper industry embraced the ideal of professional journalism. Newspapers now strived to be objective and fact-based. Once the news was more accurate, fake news was no longer on the public’s mind and the term faded away.

Roman Emperors used coins to spread news. Caesar’s coins reinforced his claim that he descended from the goddess Venus.

Even though the term fake news went into hibernation for most of the 20th century, the spread of fake news never stopped. People still created misleading information that masqueraded as legitimate news, but it was usually called propaganda.

In the mid 1990s, the term fake news emerged from its slumber. This time, it was re-purposed to describe satirical newscasts on American television. Such fake newscasts created satire by mixing current events with critical humour and serious commentary.

Canadian-born comedian Norm Macdonald was key in bringing back these words. The host of Saturday Night Live’s Weekend Update from 1994-1997, he would open each newscast with “I’m Norm Macdonald, and now, the fake news.” With almost 10 million weekly viewers, Macdonald mainstreamed fake news as a description for fun, satirical news.

Shortly after Macdonald left Saturday Night Live, The Daily Show with Jon Stewart debuted on Comedy Central. Another fake news show, it became popular for its critical political content. While staff would privately call the show fake news, Comedy Central didn’t publicly embrace the label until 2004.

At the time, American news network CNN branded itself “The most trusted name in news.” During the 2004 Republican National Convention, Comedy Central played on CNN’s slogan by setting up a large billboard near the convention centre that pronounced The Daily Show as “The most trusted name in fake news.” The move further cemented fake news in the public’s mind as a form of satire.

Britain’s Benny Hill was an early creator of fake TV newscasts. He often used burlesque to satirise the news.

Barely a decade passed before fake news began to be associated with its original meaning of bad, deliberately misleading information. In 2014, online disinformation expert Craig Silverman was running a research project on plagiarised and fabricated news. Spotting a false story on National Report, he labelled it “fake news” and posted it to Twitter. The tweet didn’t get much attention, but it was the beginning of Silverman using fake news in its original sense: as he defines it, “people or entities who consciously lie for profit and propaganda.”

As Silverman’s project carried into 2016, he and his colleague Lawrence Alexander discovered Macedonian-based websites that were spreading deliberately misleading news that favoured then-presidential candidate Donald Trump. They wrote about it for Buzzfeed on November 3rd of that year. The story went viral, and Google searches for the words “fake news” skyrocketed. Fake news was back on the public’s mind as a term for false or misleading news reports, just like it was with newspaper readers of the 1800s.

Only a month later, the meaning of fake news further evolved. This time, the change was drastic and profound. On December 10th, then president-elect Donald Trump took to Twitter to describe a CNN story that he would stay on as executive producer of reality TV show The Apprentice while in office as “FAKE NEWS!!!”

To be sure, the CNN story had factual errors. Importantly though, the errors did not appear to be deliberate. CNN based their story on a report that appeared earlier that day in Variety.

From here Trump continued to use the term, transforming it into a catch-all description of many legacy journalistic organisations such as The New York Times and NBC News. In fact, during his first term as president he used “fake news” approximately 2,000 times. It caught on, and many people now regularly use it to discredit news organisations.

The term fake news, thus, has come to have at least three uses today. First, it can be deployed to describe news reports that appear real but are maliciously intended to mislead people. Think Macedonian websites knowingly peddling falsehoods as real news. Second, it can be deployed to describe fun or mischievous satirical news. Think Weekend Update offering a humourous version of the news. Third, it can be deployed in a pejorative sense to discredit and undermine trust in professional journalism. Think Donald Trump suggesting that some reports or even entire news organisations are little more than purveyors of false information.

Consumers of news and current events have good reason to be attuned to every possible meaning of fake news. In fact, our media literacy depends on knowing how the term is being used in any given context.

The coming pages focus on the fun: we will consider fake news that is mischievous and satirical. Such fake news has the possibility to mislead, but unlike more nefarious forms of fake news it is not out to maliciously fool people. Rather, its creators generally have good intentions.

Journalism is a watchdog on all of society. To be a good watchdog, quality journalism sticks to some basic principles: independence, inquiry, and fact verification.

Independence means that journalists should be free from influence—be it from government, corporations, or even media owners—to pursue stories wherever they find them. Inquiry means that journalists should ensure that all relevant avenues of a story are covered. Verification of facts means that journalists should check that their report is true. When journalism embraces these principles, we can feel more confident in the news that we consume.