Menu

Menu

Menu

Menu

Punishment exists when laws are broken. But what kind of punishment is most appropriate to bring about justice?

The historical importance of Hammurabi’s Code cannot be understated. However, what should not be lost in this consideration of individual laws, relief sculptures, and varying translations is that the stele in the Louvre that contains Hammurabi’s Code is to the world today the most comprehensive attestation we have of Hammurabi’s dedication to justice. And perhaps more importantly, it is also the most comprehensive attestation of Hammurabi’s conception of justice.

What we determine as a society to be “justice” is a fluid and debated concept. Justice envelops varying ideas of how society can treat all people fairly.

One component of a justice system is how we punish wrong-doers. Hammurabi’s Code—much like the laws handed down from God to Moses—largely focussed on punishment. There were two types of punishment in Hammurabi’s Code:

However, there is a third concept of consequences: restoration. It was predominant in the development of Aboriginal Law.

To understand the Aboriginal concept of consequences, it is first important to understand the Aboriginal worldview. The Aboriginal worldview can be linked to a hierarchy based on dependencies. Mother Earth is first since everything and everyone depends on the earth for survival. The plant order is next since the animal world needs plants to survive. After that comes the animal order. Humans, dependent upon all these levels, are the least powerful and least important power in creation. Harmonious interconnections are required between these orders for long-term survival.

Traditional Aboriginal laws reflect these ideas. Because each citizen can contribute to the effective and sustainable welfare of the entire community, traditional Aboriginal conflict resolution has been guided by spiritual means nurtured by customs and habits. Sweats, isolation, and the teachings and influences of Elders, parents, and grandparents are examples of this. Important to Aboriginal systems of laws are notions of honesty and harmony brought about by forgiveness, restitution, and rehabilitation. These three factors contribute to the restoration of smoothly operating families and communities.

Restorative justice envelops these ideas. Restorative justice recognizes that everything is connected, and a crime disturbs the harmony of these connections. When a crime takes place, its remedy should be determined by the needs of victims, the community, and the offender. This restoration is meant to heal victims and communities, while encouraging offenders to confront the consequences of their action. Such an approach is believed to lead to restoration for all.

Retribution, restitution, and restoration are three schools of thought about how consequences should be delivered when laws are broken in Canadian society. As can be seen, none of these ideas are mutually exclusive. And because all crimes involve unique circumstances, it is difficult at the outset to prescribe what consequence is most appropriate for each crime.

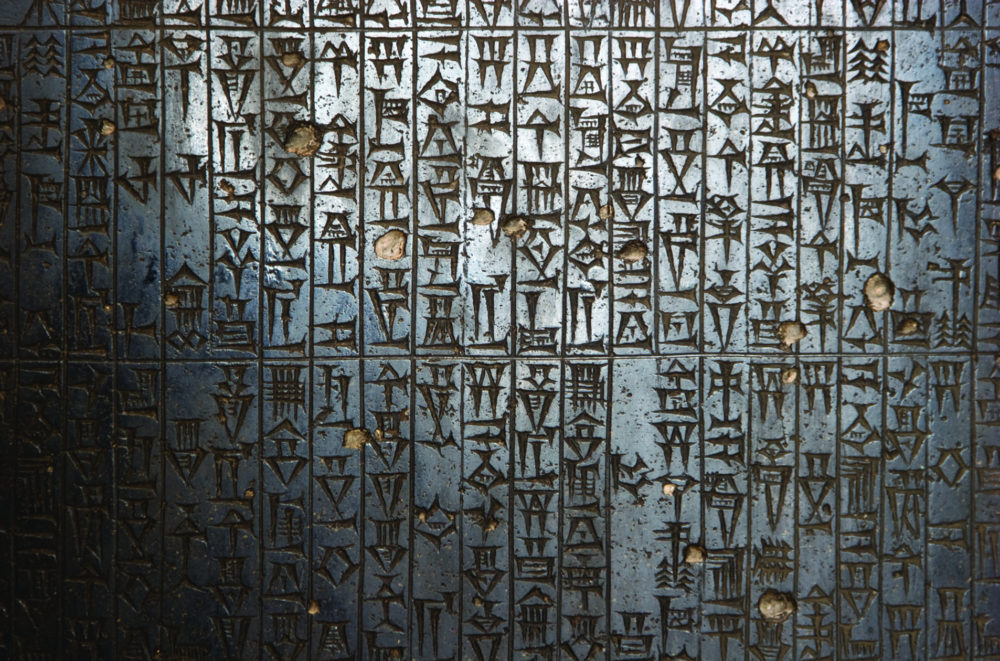

Cuneiform text of Hammurabi’s Code. Cuneiform writing began with the ancient Sumerians (c. 3500-3000 BCE) who created pictograms (a drawing of what is being depicted). Writing evolved into logograms (a picture representing a word) and then phonograms (a character representing a vocal sound). Hammurabi’s Code used phonographic cuneiform.

Several hundred years after Hammurabi, Moses came down from Mount Sinai with the Mosaic Laws. Mosaic Laws include the Ten Commandments and other laws set out in the Old Testament. Although Mosaic Laws view crimes as acts against God, they have many similarities to Hammurabi’s Code. In fact, ever since the Code was dug up, people have debated whether Mosaic Laws were partially based on Hammurabi’s Code.

One side believes that their commonalities are not conclusive evidence that Hammurabi’s Code was the source of Mosaic Laws. They point out that similar situations will often emerge in all societies. These situations ultimately require the development of similar laws. They also note that there is a relatively large stretch of time and geography between the two codes of law.

The other side of the argument is less accepted. They believe that Mosaic Laws were at least in part a re-invention of Hammurabi’s Code. They point out that there are many similar laws, with some being almost identical. They also have noted similarities in the broader themes and general structures of both codes.

Regardless of one’s belief about the source of Mosaic Laws, it is clear that we can understand much about the evolution of justice by looking at codes from past ages such as Hammurabi’s Code and the Mosaic Laws.