Menu

Menu

Menu

Menu

A century ago, direct democracy almost became the way we make laws in Saskatchewan.

In the late 1800s, many midwestern Americans were demanding ways to keep the elite in check. Politicians listened, and by 1911 thirteen states legislated forms of direct democracy. There were three common types:

To trigger a recall, initiative, or a referendum, people would circulate a petition. If enough signatures were collected (usually around 8-10% of voters), a vote would be held.

American zeal for direct democracy crept into Saskatchewan. The Trades

and Labor Council of Regina and the Saskatchewan Grain Growers’

Association began to lobby for direct democracy. Politicians heard the

demands, and in the 1912 provincial election both Liberals and

Conservatives promised some form of direct democracy.

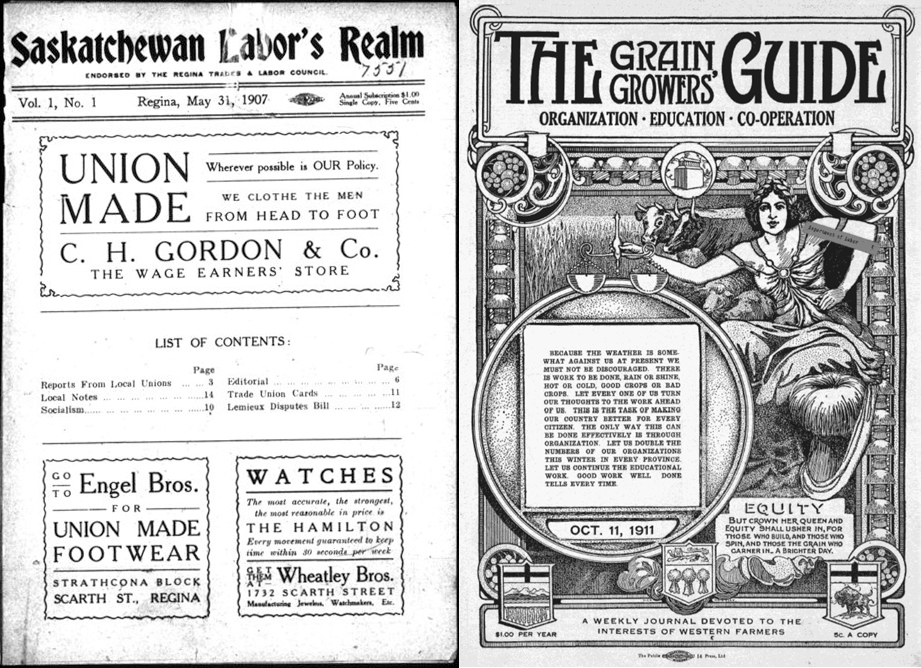

Saskatchewan Labor’s Realm and the Grain Growers’ Guide—the widely read newsletters of the Trades and Labor Council of Regina and the Saskatchewan Grain Growers’ Association—often lobbied for direct democracy.

Liberals won the election, but were uneasy about direct democracy. They feared that it gave the masses too much power. Premier Walter Scott privately asked party representatives to pour cold water on the idea at local constituency meetings.

Nevertheless, an election promise cannot be easily thrown away. So Liberals introduced The Direct Legislation Act. The bill received unanimous approval by all parties in the 1912-1913 legislative session.

The Direct Legislation Act allowed for referendums and initiatives, with the following requirements:

Under the legislation, citizens could not use direct democracy powers to force the government to spend money, nor could they force the government to change tax laws.

The powers in The Direct Legislation Act were not immediately put into effect. Instead, a referendum was held. If at least half the ballots were cast in favour, and at least 30% of Saskatchewan’s 161,561 eligible voters showed up to cast a ballot in favour, there would be direct democracy in Saskatchewan.

The government suppressed voter turnout by scheduling the referendum at the tail-end of the busy harvest season, in November 1913. This gave supporters little time to drum up interest. As well, the government did the bare minimum to promote the referendum.

On referendum day, 32,133 ballots were cast. 26,696 votes in favour (83%), 4,897 votes against (15%), and 540 spoiled ballots. Despite the landslide of votes in favour, the voter turnout threshold was not met: only 16.5% of all voters in the province said yes to direct democracy. The Direct Legislation Act never came into force.

After the referendum, Premier Scott said “The notable lack of interest taken in the matter as disclosed by the poll goes to show that the people of this Province are not sufficiently advanced to have the laws of the Province made under the plan of Direct Legislation.” His message was clear: citizens were not interested enough in direct democracy to make it workable.

Despite Scott’s dislike of direct democracy, his government called a referendum on prohibition in 1916. In fact, since the rejection of The Direct Legislation Act, the province has initiated eight plebiscites and referendums. However, it would not be until 1991 that Saskatchewan voters were given the power to force a provincial vote with the passage of The Referendum and Plebiscite Act.

There are many reasons why citizens should directly decide an issue.

Sometimes an issue is so foundational, it can be difficult for the government to move forward without a clear mandate from the people. A good example is the 1992 proposal to amend Canada’s constitution. Every major political party was in favour. However, the general feeling was that Canadians themselves should decide through a referendum. A referendum ensured that our highest law would change only if a majority of Canadian citizens approved.

Other times, an issue does not fit into party politics. For example, in the early 20th century opinion was divided on prohibiting alcohol. Political parties were reluctant to take a firm stand, because no consensus existed amongst party members or party supporters. To break the gridlock, the people were asked to decide. This helped keep political parties united, and ensured the majority would get its way.

Regardless of the reason for holding a plebiscite or referendum, they can be a useful decision-making tool.