Menu

Menu

Menu

Menu

What happens when fate creates a new society?

We are all individuals. Yet, we are individuals as part of a larger society. A society consists of people who share traditions, institutions, and interests. These usually evolve organically overlong periods of time. Occasionally, circumstances will force a quick creation of a society. For example, when there is a shipwreck, the castaways need to find ways to live together. So they will form a new, temporary society.

Some castaway societies have functioned quite well. Others have failed abysmally. Recent books such as Nicholas Christakis’ Blueprint and Rutger Bregman’s Humankind have shed some light on why. Obviously, access to food, water, and shelter helps. Less tangible reasons are equally important. How the castaways organise themselves, the tone set by their leaders, and their willingness to cooperate and care for one-another all play vital roles.

To begin understanding why some castaway societies succeed and others fail, let’s journey into two shipwrecks with two very different outcomes. They can provide hints for how we approach ourselves today as individuals and as a society.

Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa [Scène de Naufrage], 1818-1819. To create the painting, he interviewed survivors and built a model raft.

Viscount Hugues Duroy de Chaumareys was a sailor past his prime. But he was also a member of the French aristocracy. Such connections were qualification enough to be made captain of the Méduse. On June 17th 1816, Chaumareys set sail to Africa, along with roughly 400 French officials and crew. They were to take control of Senegal from the British. Chaumareys turned over navigation to an equally unskilled seaman. The two ignored expert advice, took an unsafe route to save time, and on July 2nd ran the Méduse aground on a sandbank 50 kilometres from the shore of Mauritania.

At first, the plan was to ferry everyone to land in lifeboats. However, a harsh storm led to fears that the Méduse would break up before the rescue was complete. So they concocted a scheme to build a 140 square metre raft, fill it with passengers, and tow it to land with lifeboats. About 250 people, packing luxury goods, boarded lifeboats. Chaumareys was carried onto his lifeboat in an armchair. Meanwhile, close to 150 people were forced at gunpoint onto the rickety raft. 17 crew members stayed on the marooned ship.

The upper brass in the lifeboats soon decided that towing the raft was jeopardising their own chances of survival. They cut the raft loose, ignoring the passenger’s desperate pleas. They safely rowed to shore, and carried on to Senegal over land.

The raft quickly devolved into chaos. People clamoured for safety in its centre, the weakest were thrown overboard to preserve rations, and when deep hunger set

in so did cannibalism. After two chaotic weeks, another French ship following the proper route to Senegal discovered the raft adrift at sea. Only 15 men were left.

In Senegal, Chaumareys grew worried about valuables left behind at the wreck site. In August, he sent a salvage mission to the sandbar. When the salvagers arrived, to their shock they found the Méduse intact. Inside, three crew members were still alive.

The last incoming passenger and crew manifest of the Julia Ann, upon its arrival in Sydney on July 24th, 1855.

Captain Benjamin F. Pond was no stranger to the sea. But he was no match for a faulty map. When he set the Julia Ann out from Australia en route to San Francisco on September 7th 1855, he had no idea that his map would lead to 56 passengers and crew stranded on the Scilly Islands, near Tahiti.

The Julia Ann’s passengers were mostly Mormons. Mormons knew Pond and his crew were kind, so this was the second time he was hired to transport them to America. From the moment on the night of October 4th when the ship sailed straight into a coral reef, Pond lived up to his reputation. He set a tone that would

guide the castaways to survival and eventual rescue.

A COMMON BROTHERHOOD SHOULD BE MAINTAINED

As the boat sat capsized on the reef, Pond organised an evacuation to a nearby rocky island. Amidst the efforts, he spotted the second mate salvaging a bag of gold. He ordered the mate to abandon the gold and focus on getting children ashore. In a more questionable decision—albeit one that enforces the idea that the vulnerable should be prioritised— when the crew discovered that a passenger had abandoned his family on the boat, they threw him into the ocean. He managed to swim back, and was allowed to stay.

In total, five lives were lost. The survivors soon settled on a larger island, where Pond told them that “a common brotherhood should be maintained.”

To maintain a “common brotherhood,” the castaways shared worked in ways that best-fit each individual’s skill. They salvaged what they could from the wreck, found food and water, built shelters, established a lookout for passing boats, and even developed recipes to keep their diet interesting. Children were given play time, and all provisions were shared equally. Meanwhile, they repaired and modified the lifeboat so that some crew could journey to the nearest populated island, Bora Bora, 350 kilometres away.

On December 3rd, with the lifeboat fixed and the winds favourable, Pond and much of the crew set out to sea. Four days later, they were arranging a rescue mission on Bora Bora, and the survivors were soon picked up. Despite the wreck, the Julia Ann survivors remained forever grateful to Pond for his leadership and kindness.

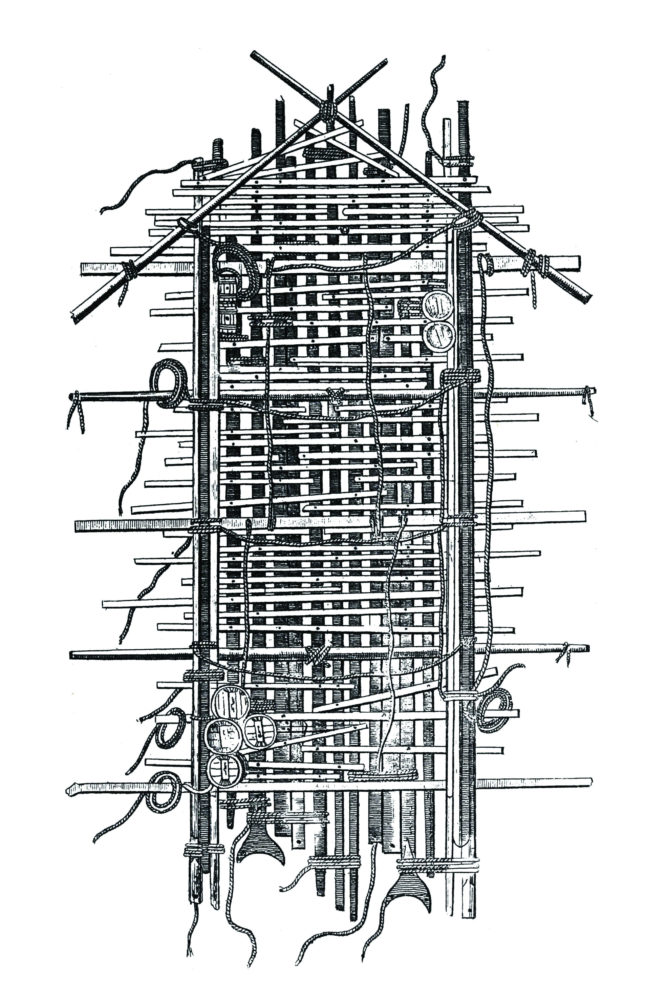

Plan of the Raft of Medusa, created by survivor Alexandre Corréard.

Quite possibly, almost everyone could have survived the wrecks of the Méduse and the Julia Ann. Yet it was only the wreck of the Julia Ann that ended happily.

Why is this?

One reason is that Captain Pond exhibited caring and cooperation, while Captain Chaumareys exhibited cruelty and selfishness. In fact, Pond became a legend in Mormon lore. Chaumerays ended up in jail.

This can help us understand why leadership and tone are important, to the outcomes of shipwrecks and to the outcomes of societies. The Captain Chaumareys approach— blind self-interest that leaves everyone fighting to survive— stands in sharp contrast to the Captain Pond approach—kindness and “brotherhood” that values people over money, and pays attention to the vulnerable.

Which kind of society would you rather be a part of?

The fact that we live together appears to be an ingrained aspect of human nature. Everywhere people are found, we form into collective groups and create societies. This is true for the Inuit, the Mâori, the Celts, and the Tjimba, along with everyone else.

There’s no simple explanation for this. That understood, genetics— the building blocks of human heredity—can offer a hint.

Genetically, all humans are 99.9% the same. This is true regardless of our race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, gender, sexual orientation, age, or mental or physical abilities.

Because we are all so similar, we share many traits. One shared trait across humanity is the tendency to group together and create societies.