Menu

Menu

Menu

Menu

When the Batavia wrecked, one man emerged with all the power. He used it ruthlessly.

On the night of June 4th 1629, the Batavia was dangerously off-course. When the midnight watch spotted surf breaking in the distance, the skipper wrote it off as glimmering moonbeams. Neither man knew that the Dutch vessel, en route to Jakarta, was a mere 80 kilometres west of Australia. Minutes later, the Batavia smashed into a coral reef.

As the ship ground against the rocks and listed, the skipper desperately ferried people to a nearby island. Of the 340 passengers and crew, only 300 survived that chaotic night.

When day broke, the skipper realised he quite literally hit the Houtman Abrolhos. The small island chain could not support much life, so he packed over 40 senior crew members into a longboat to search Australia for water. When the search came up dry, they continued on to Jakarta to send a rescue ship.

Back on the islands, there was only one senior official left: Under Merchant Jeronimus Cornelisz. Cornelisz ruled as head of a council, and preached a bizarre libertine

doctrine that claimed people should not worry about doing evil.

Cornelisz was certain that a rescue ship would come. Having little conscience, he hatched a plan to take it over, load it with the Batavia’s salvaged wealth, and go pirating across the seas. For his plan to work, he needed to cull the castaways down to about 45 loyalists.

When two men were caught stealing wine, Cornelisz seized the moment to start the cull. He sentenced them to death. When the councillors pushed back, he dismissed them all and formed a new council of loyal mutineers. The mutineers signed an oath of loyalty and carried out the death sentences. Cornelisz then began looking for ways to kill more castaways.

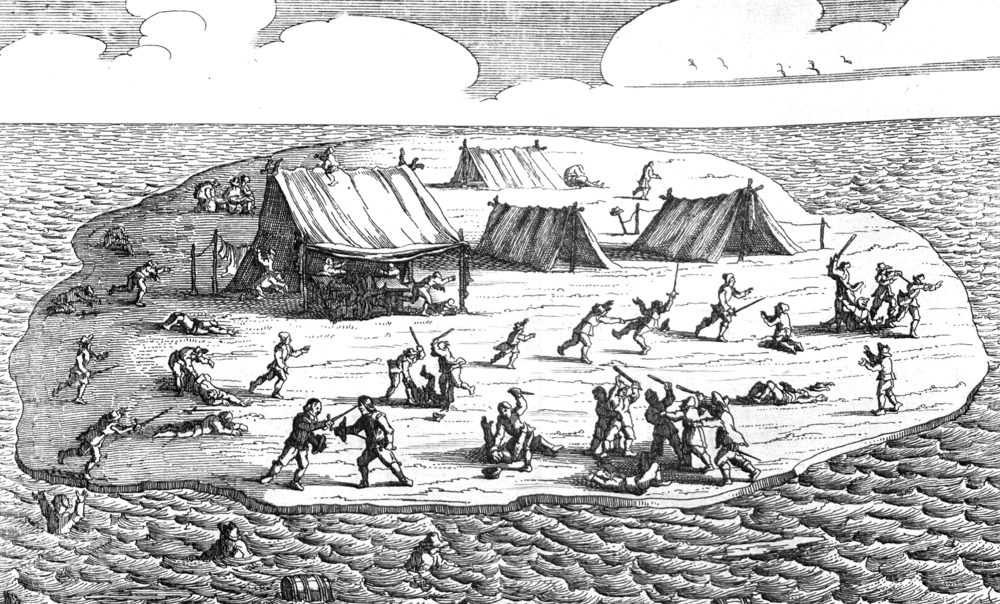

Massacre of Batavia survivors from the 1647 Dutch book Unlucky Voyage of the Ship Batavia.

Soon, murder became a rite of passage to prove loyalty to Cornelisz. Often the choice was kill or be killed. However, the process was slow, so Cornelisz shipped small groups of castaways to nearby islands. He promised to send supplies but never did, believing they would starve.

When the exiles found enough food and water to live, Cornelisz sent teams to kill them. Eventually, 50 survivors made their way to a larger island on makeshift rafts or by swimming.

These rivals did not know Cornelisz’ motivation, but they knew he wanted them dead. They armed themselves with sticks, stones, and items washed up from the Batavia, which allowed them to rebuff two invasions by Cornelisz’ men. In fact, they managed to kidnap Cornelisz on his third mission to the island.

Determined to rescue their leader and finish off their rivals, Cornelisz loyalists launched a fourth offensive on September 17th. The battle was abruptly interrupted by a sight on the horizon. The rescue ship had arrived. Both sides raced to reach it: the mutineers hoped to overthrow the ship, the rivals hoped to warn the rescuers of danger. The rivals got there first.

Trials were immediately held. With plenty of witnesses and a signed mutiny agreement, it was not hard to ascertain guilt. Cornelisz and several mutineers were executed on the island. Others were taken to Jakarta for the governor to decide their fates. And two men were abandoned on Australia, becoming its first permanent Europeans settlers.

In the end, the mutineers killed an estimated 120 people. This is to say nothing of deaths from accidents and illness, and the death sentences handed out in the trials. With only about 120 survivors, the Batavia is known today as history’s bloodiest mutiny.

It is dangerous to put too much power in too few hands. This is what happened with the Batavia wreck. When the skipper and senior crew left, Cornelisz was free to take absolute control. Nobody else had the power to put him in check, and the castaways as a whole could not vote him out of power. Cornelisz ruled through violence and intimidation, and only violence and intimidation could stop him.

Cornelisz, in other words, was a dictator.

Canada has found ways to help avoid such a fate. The ability to create laws is spread across federal, provincial, local, and First Nation governments. Institutions like courts and the central bank are designed to be free from political interference. And above all, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees the democratic rights of every citizen. In Canada, no single person can hold unrestrained power.