Menu

Menu

Menu

Menu

A radio show meant to fight bigotry mutates into a fascist movement.

Father Charles E. Coughlin dreamed of building a great church. In 1926, the Bishop of Detroit gave Coughlin the opportunity. He assigned him to the Shrine of the Little Flower.

Father Coughlin arrived to a warm welcome from the small suburban congregation. A much hotter welcome came from the Ku Klux Klan, who burned a cross on the church yards. Coughlin used this act of hate to convince WJR radio to give him a weekly show. After all, a little church fighting bigotry would make for great radio.

Coughlin put his remarkable oratory skills to work, and donations poured in from across the WJR listening area. He used the donations to buy airtime on other stations. The more airtime he bought, the more money flowed in. By the 1930s, Coughlin’s radio ministry expanded to nearly 60 stations across America. His show was a Sunday staple for 30 million listeners.

Part of Coughlin’s appeal was his ability to enrage listeners. The angrier he made them, the more they listened. Preaching as the Great Depression set in, he’d make reasonable demands—such as debt relief or worker’s rights—and then tack on a torrent of hate, usually targeting politicians.

In 1934, Coughlin turned his show into a political movement: the National Union for Social Justice. Cleverly named—who would say that social justice is bad?—he promoted 16 principles, reminiscent of Italy’s fascist constitution. Local chapters popped up across America, and by 1936 he was ready to contest the presidential election. A North Dakota congressman was declared his Union Party’s candidate, but Coughlin was in charge.

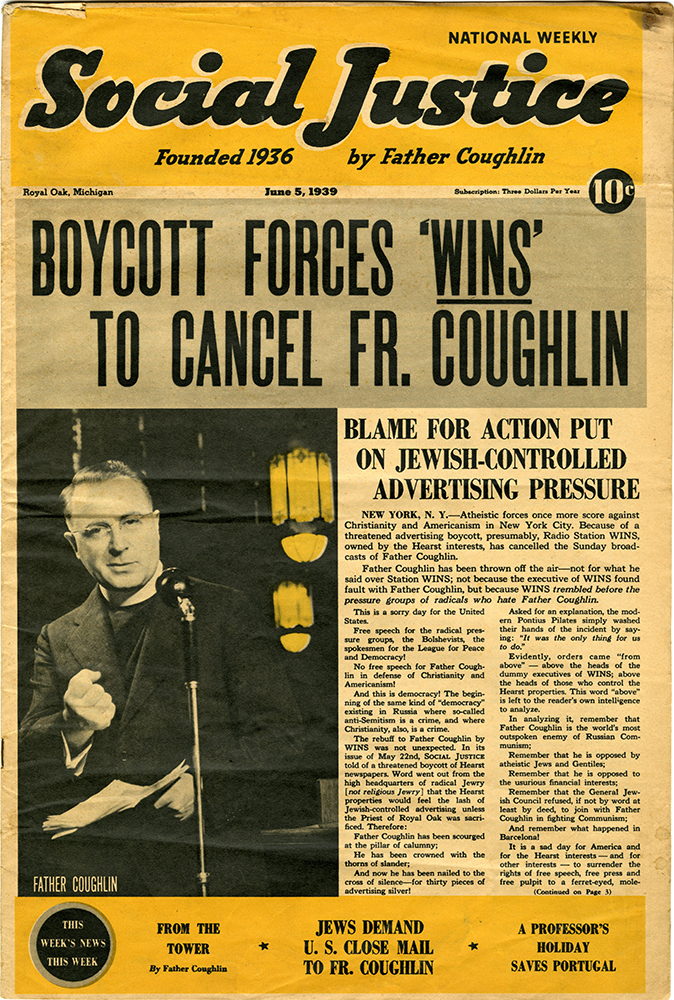

Social Justice, June 5th, 1939. Coughlin and his fanatics accused Jews of everything from controlling the banks to starting World War II.

Many feared that Coughlin was trying to create a dictatorship. Now being escorted by a paramilitary, he’d scare people into believing America was on the brink of communism, demand that Jews proclaim loyalty to his principles, and threaten “bullets over ballots” if he lost the election. At the national party convention, a lone delegate warned 10,000 Coughlin supporters about the emerging mob psychology. The crowd chased him out.

Thankfully, Coughlin’s on-air popularity and rabid following didn’t translate into electoral success. He only received 2% of the vote. In fact, a later opinion poll said 75% of his listeners disagreed with him.

Filled with hate towards Jews, Japanese-Americans, and Britain, it sold a million copies a week.

The loss spiralled Coughlin into deeper fanaticism. When he started to preach that Jews were to blame for their Nazi persecution, several radio stations dropped him. In response, Coughlin followers staged protests outside the stations. Nevertheless, radio wasn’t his only outlet. He

also founded Social Justice magazine. Filled with hate towards Jews, Japanese-Americans, and Britain, it sold a million copies a week.

In 1938, Coughlin fanatics independently formed The Christian Front, a violent antisemitic group. Coughlin refused to condemn them. In 1940, 17 Fronters were put on trial for a plot to overthrow the government. They were acquitted, but the trial led to the Front’s disintegration.

By 1940, the National Association of Broadcasters—the trade association of America’s radio stations—had enough of Coughlin’s runaway preaching. They updated their Code of Standards so that he would be forced off the air. Around the same time, the Postal Service banned Social Justice from the mail, saying it violated the Espionage Act. Coughlin was still free to preach his terrible ideas, but his ability to spread them was being curtailed. Meanwhile, the government launched investigations into him with cooperation from his church superior.

With no radio show, no magazine, and no church support, Coughlin simply faded into obscurity. He returned to preaching at the Shrine of the Little Flower. Coughlin retired in 1966 and died in 1979, never having renounced his crusade.

America’s governmental radio broadcasting regulator—the Federal Communications Commission—ignored Father Coughlin. They believed their responsibility was to regulate technical aspects of the new medium. Radio stations were left to self-regulate content. This is how Coughlin stayed on the air until 1940, when the National Association of Broadcasters banned him.

For the Catholic Church, Coughlin posed a complex problem. The Vatican considered him a local issue, but the only American Catholic with the power to remove him—the Bishop of Detroit—supported Coughlin. When prominent Catholics spoke out against Coughlin, his fanatics unleashed a torrent of hate. It was only when the Bishop of Detroit died in 1937 that the Church reeled Coughlin in. The new Bishop censored him, cooperated with federal investigators, and ultimately—although perhaps belatedly—ordered him to stop all national politicking in 1942.