Menu

Menu

Menu

Menu

Like a prairie fire, the KKK burned through the province in the late 1920s.

During the 1910s, the Ku Klux Klan was making a comeback in America. In 1921, recruiters crossed the border. Canada was not immune to its advocacy for White Protestants above all others. Soon, local lodges called Klaverns popped up from the Maritimes to British Columbia.

One Indiana Klansman, Pat Emmons, set his eyes on Saskatchewan. With immigration changing the province’s British-Protestant make-up, in late 1926 Emmons caught a train to Moose Jaw and started recruiting.

By 1927, Emmons had sold some 25,000 memberships.

By 1927, Emmons had sold some 25,000 memberships. The province’s Klan was linked to the American organisation, but the local members soon demanded local control. In response, Emmons simply vanished with all the Saskatchewan Klan’s money.

Saskatchewan’s Klan was now penniless. But it was not defeated. Members regrouped, severed all ties with the American Klan, ditched the white robes, disavowed violence and lynching, and set out to maintain a “British” Saskatchewan.

The Klan’s view of a “British” Saskatchewan was unfortunate, to say the least. They took the nonsensical position that minorities should have the same rights as everyone else yet they also should be segregated from the rest of society. They opposed non-British immigration. They created a “culture war” against Catholic schools. And they were hostile to Asians and the few Blacks in the province.

Curiously, the Klan had no interest in Indigenous people. This may be due in part to the era’s segregationist reserve system, with Indian Agents able to limit Indigenous peoples’ mobility.

From its arrival, Saskatchewan’s premier Jimmy Gardiner fiercely opposed the Klan. Like the KKK, Gardiner favoured a “British” Saskatchewan, though he argued that the Klan’s intolerance was un- British. By contrast, his Liberal government was warm to minorities and immigration, so long as they were European minorities. Sadly, white supremacy was common in the 1920s.

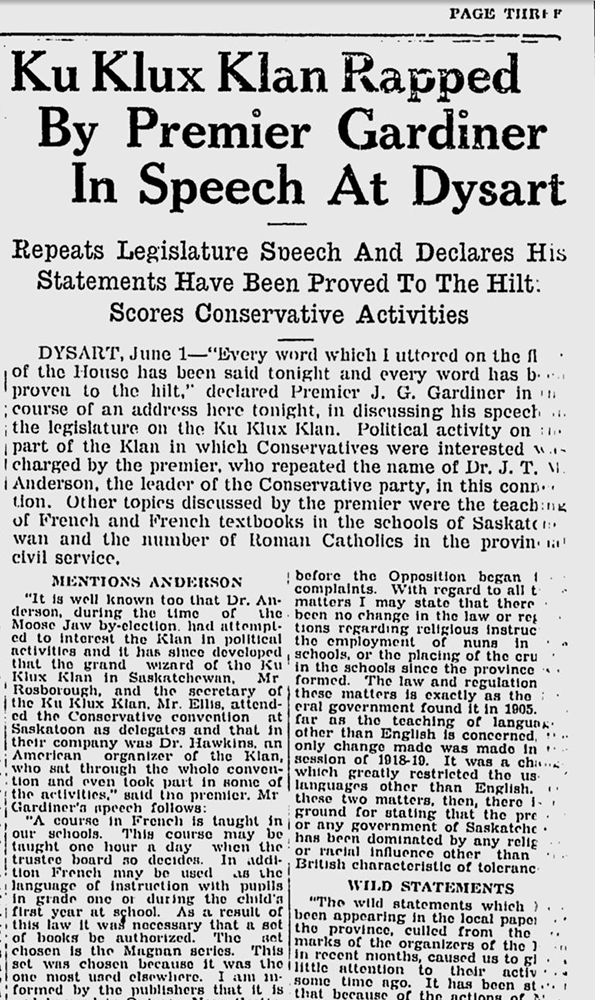

Saskatoon Phoenix, June 2nd, 1928. Premier Gardiner toured the province to denounce the Klan.

Gardiner’s fight against the Klan became central to the looming provincial election. The Liberals had been in power since the province’s founding. With the opposition parties weak and divided, people saw the Klan as a vehicle to oust a tired government. Klan rallies filled community halls and stirred up political firestorms, with entertaining and sometimes vulgar speakers going after the “elite.”

The Conservatives and the Klan soon cozied up. They had no formal arrangement, but the Conservatives went into the June 1929 election with Klan support. Add to that, the Conservatives formed non-compete agreements with the Progressive Party and Independent candidates. In 47 constituencies, opposition to the Liberals was united behind one candidate.

Klan issues such as immigration and Catholic schools dominated the campaign, and it worked. On election day, Conservatives and their allies took enough seats to form a government. The new government enacted some policies to please the Klan, such as restrictions on Catholic schools.

Despite having allies in government, Saskatchewan’s Klan soon fizzled out. Oddly, having allies in power was one reason for the Klan’s demise. The Klan was largely built around opposing people in power. With the new government Klan-friendly, who was there to now oppose? Even more devastating to the Klan’s cause was the Great Depression. It led to a halt on immigration, taking away a major critique of the Klan. Further, as the land dried up, people couldn’t afford to eat let alone pay for Klan memberships.

By 1931, the Klan no longer served a purpose. So as quickly as the Klan rose in Saskatchewan, it largely vanished.

Premier Gardiner may have overplayed his attacks on the Ku Klux Klan. He would draw equivalencies between the American and the Saskatchewan Klan, claiming Saskatchewan’s Klan endorsed violence and wore white hoods.

After 1928, Saskatchewan’s Klan continued to engage in cross burnings and acts of bigotry. However, they did not wear hoods, did not undertake lynchings, and swore to obey the law.

Gardiner’s hyperbolic accusations gave the Klan a boost. It allowed the Klan to portray themselves as victims. His vigorous critique also hardened social divisions along religious lines, leading some non-British Protestants to support the Klan.