Menu

Menu

Menu

Menu

The Damage and the Reporting

When the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the immediate reaction—especially in the United States—was one of triumph. This public reaction was partially created by the U.S. military. They portrayed the bombings around two premises:

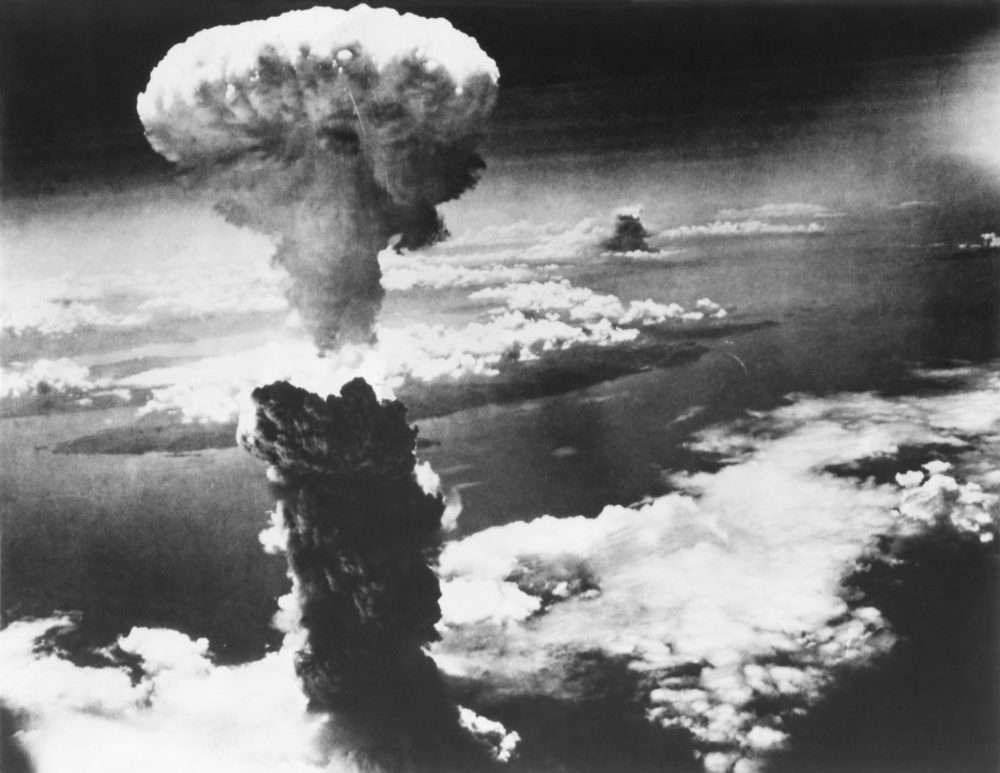

The media largely followed the American government’s line. This led to news reports that largely ignored the unprecedented suffering and damage on the ground, as newspaper reports and magazine spreads glorified the mushroom cloud in words and pictures.

Contrary to U.S. reports, however, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not military bases. They were cities similar in size to Denver or Portland. The damage was extraordinary, especially in human terms. Of the two cities, Hiroshima sustained the worst harm. Almost everything and everybody within a two-kilometre radius of the explosion in Hiroshima perished. The massive death and destruction on the ground was due to several factors:

So while the destruction of property was phenomenal, even more shocking was the death, injury, and suffering experienced by civilians.

Mushroom Cloud of Atom Bomb exploded over Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, 1945. World War 2.

The first comprehensive report to emerge in Western media about the ground-level impact of the blast came from Australian war reporter Wilfred Burchett. Burchett managed to get to Hiroshima before the official American media convoy. His report “The Atomic Plague” appeared in the September 5, 1945 London Daily Express. It was not approved by American military censors. While the article discussed the physical damage, more central to the piece was Burchett’s “warning to the world”: his graphic descriptions of how people—even those untouched by the initial bombing—were falling ill and dying from sores, bleeding, and flesh that started “rotting away from the hole” created by vitamin injections given to survivors. Even Burchett himself fell ill with radiation poisoning. He spent several days in a military hospital. Upon his release, he discovered that the film from his camera had been confiscated.

The American media—in conjunction with the American military—tried to dispel such reports. For example, The New York Times reported on September 12 that stories of radiation poisoning were nothing more than “Japanese propaganda.” These reports were written despite the fact that many of these reporters had visited Hiroshima. In fact, General Groves, the military head of the Manhattan Project, went so far as to say that even if there was radiation poisoning, doctors claimed “it is a very pleasant way to die.”

However, by 1946 it was becoming increasingly impossible for the official narrative to carry on. Foreign and domestic media reports were starting to outline human suffering from radiation poisoning. Meanwhile, a handful of official government reports theoretically outlined how radiation from atomic bombs could cause human suffering. And perhaps most importantly, there were American journalists who had seen the suffering in Hiroshima first-hand during their U.S. Military-overseen trips but had not reported on it.

A report by journalist John Hersey is widely acknowledged as the work that finally changed the American public’s understanding about what happened in Hiroshima. Hersey was sent to Hiroshima in May 1946 to report on the aftermath of the bomb for Life and The New Yorker. He went there with the belief that an atomic bomb should never be used again, and what Hersey learned dramatically confirmed his belief. After spending three weeks interviewing survivors, he chose six of their stories for his 31,000 word article simply titled “Hiroshima.” It graphically recounted their experiences in a plain and detached language, conveying facts with little mediation. Hersey later claimed he chose this style of writing so “the reader’s experience would be as direct as possible.”

The New Yorker’s editors believed that “Hiroshima” was of incredible public importance. They decided to devote the entire August 31, 1946 edition of the magazine to Hersey’s work, instead of their original plan to print it in four parts. The New Yorker also reached out to other media to ensure “Hiroshima” received the widest-possible audience. Following its widely-publicized initial publication, “Hiroshima” was offered for reprint to other newspapers, ABC was granted free broadcast rights, and by November it was printed in book form and being given away by the Book of the Month Club. These efforts worked. “Hiroshima” became a nation-wide sensation, with an overwhelmingly positive response.

“Hiroshima” dramatically reshaped American understandings about the atomic bomb. Its widespread publication worked to end the U.S. military’s official narrative about the atomic bombing of Japan. By telling the story from the ground, it forced the public to consider the bomb from a perspective other than the view from the air while debunking the military line that the army simply attacked military bases.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the American government created The Office of Censorship. Its purpose was to keep wartime secrets from being learned by enemies, while helping to ensure domestic unity.

President Roosevelt chose Byron Price, the executive news editor of the Associated Press, as the office’s director. Price believed that censorship should be voluntary. For Price, this would get the media onside and make them part of the overall war effort.

The effort was successful. The majority of coverage of the war was upbeat, and very few breaches of the voluntary censorship code are known to have happened. One noteworthy exception, though, was a March 1944 report in a Cleveland newspaper that revealed “Uncle Sam’s mystery town” in Los Alamos. General Groves was so enraged by the story, he floated the idea of drafting the story’s writer to the Pacific Theatre of war. Upon learning the reporter was in his sixties, Groves changed his mind. The military ended up simply ensuring the story was not syndicated to other papers.

With the end of the war, the Office closed on August 15, 1945. The code was cancelled and Price famously placed an “Out of Business” sign on the office’s door. Even so, it has been reported that President Truman had secretly asked media outlets to continue following the code.