Menu

Menu

Menu

Menu

Adolph Hitler’s Nazi Germany was likely the greatest social and political setback of the 20th century. What makes Hitler’s rise to power even more troublesome is the fact the Nazis were elected into power.

There are many theories about how the Nazis came to rule Germany. Some historians point to the Treaty of Versailles, Germany’s peace agreement with the Allies following World War I. The treaty’s excessive compromises weakened the German economy and battered national morale. Others point to Black Friday, the 1929 stock market crash that triggered the Great Depression. Germany was hit particularly hard due to its economic ties with the United States. And others point out that Germany never came to a consensus on political fundamentals or human rights following World War I. The country’s post-war constitution was largely believed to be imposed upon Germany by the Allies.

These morale, unity, and economic problems following the first World War spawned radical criticism from fringe political groups. Like most liberal democracies—such as Canada or the United States today—Germany’s post-war constitution allowed radical criticism to take place in the public sphere. In Germany, the leading criticism on the far right came from Nazis.

The Nazis were a political party formally called the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei. In English, this means the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. It formed in 1920. Even though they called themselves socialist, there was very little that was socialist about the party. Hitler appropriated the word socialist as “a matter of fashion”2 to take advantage of the ideology’s popularity at the time.3 The term Nazi was used by opponents of the party, due to the word’s informal link to foolishness and clumsiness.

The Nazis promised to restore Germany to its former greatness. Underpinning this promise was a racist and anti-democratic worldview. According to historian Jeremy Noakes, Nazis believed Germany’s problems were:

fostered and exploited by the Jews through the doctrines of Liberalism with its emphasis on the priority of the individual over the community, [and the result of] democracy with its subordination of the ‘creative’ and ‘heroic’ individual to the mass, and of Marxism with its advocacy of class war.4

This critique first appeared destined for failure. The Nazis captured only 3% of the vote in Germany’s 1928 federal election. However, as German instability grew—especially economically with the onset of the Great Depression—so too did the Nazi vote. A series of four elections between September 1930 and March 1933 saw Nazi support grow to 43% of the vote and 45% of the seats of the proportionally-representative Reichstag, or German Parliament.

Within two months of the March 1933 election, the Nazi Party took absolute control of Germany. They did this by threatening and exploiting a fractured opposition, manipulating a perceived communist threat, and partnering with other far-right parties. Once they and their partners were able to control a majority of the seats in the Reichstag, liberalism in Germany was thrown aside in favour of a worldview that held that:

Every actual democracy rests on the principle that not only are equals equal but unequals will not be treated equally. Democracy requires therefore first homogeneity and second—if the need arises—elimination or eradication of heterogeneity.5

In other words, far-right thinkers in Germany believed democracy would only work if everyone was the same. Because everybody was not the same, diversity had to be destroyed. In the place of a diverse society, the Nazis idealised a singular, racially-unified German society called the Volksgemeinschaft. Such a society excluded “others.”

To build this Volksgemeinschaft and redefine democracy, Nazi thinkers set about creating a mythic and cultic rather than a rational public sphere where a grand narrative trumped facts and hatred trumped human decency. Adolph Hitler was to be this cult’s leader. Hitler put a primary emphasis on changing citizen mentalities so that the Volksgemeinschaft would be supportive of his sweeping changes to Germany’s laws and social systems. As well, he worked on psychologically preparing the German population for war.

2. Tim Stanley, “Hitler wasn’t a socialist. Stop saying he was,” The Telegraph, February 26 2014. http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/n...

3. Jewish Virtual Library. The Nazi Party: Background & Overview. www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/j...

4. Jeremy Noakes, “Introduction: Government, Party and People in Nazi Germany,” in Government Party and People in Nazi Germany, ed. Jeremy Noakes (Great Britain: University of Exeter, 1980), 2.

5. Carl Schmitt, “On the Contradiction between Parliamentarianism and Democracy,” in The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, ed. Anton Kaes, Martin Jay, & Edward Dimendberg (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994), 335

Hitler at Nazi party rally, Nuremberg, Germany, 1928.

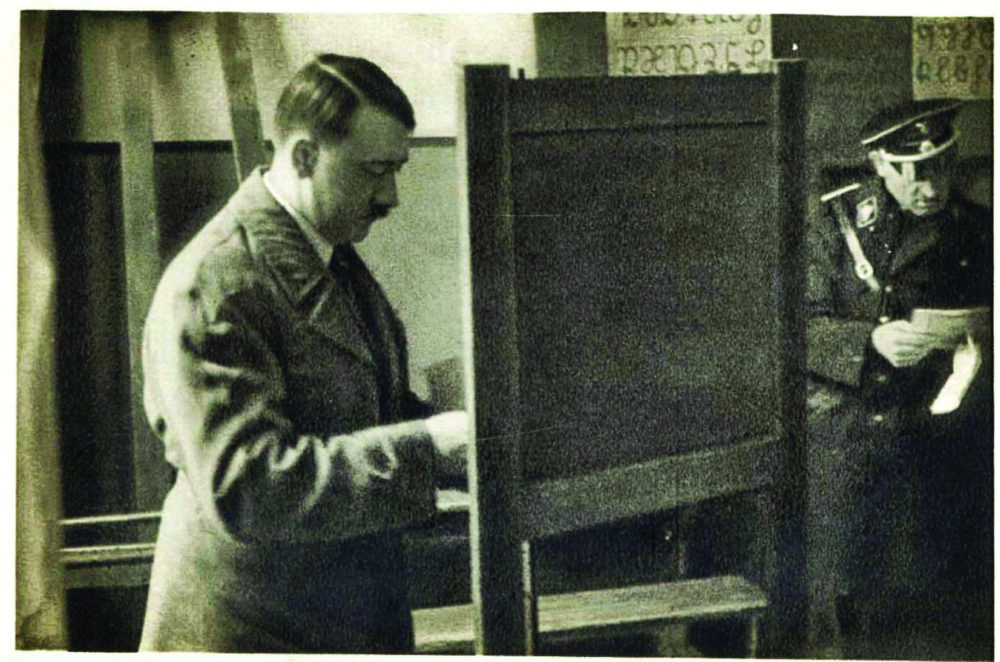

Hitler cast votes in Konigsberg, East Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russian Federation) during the March 1933 election.

Nazi Brownshirts, 1932. Some German political parties created paramilitaries who engaged in widespread street fighting. The disorder contributed to German frustration with democracy.

Marinus van der Lubbe, the Dutch Communist sentenced to death for the Reichstag fire. When the German Supreme Court acquitted four others, an enraged Hitler created a “People’s Court” where Nazi members judged treason cases.

Reichstag fire, Feb. 27, 1933. Hitler used the arson attack to suspend constitutionally-protected civil liberties. He issued the Decree for the Protection of the People and the State (the Reichstag Fire Decree). Over 1,000 Communists were arrested immediately. It remained in force throughout the Third Reich.

March 5th, 1933 was the last multi-party German election. However, this election was not free.

Hitler was already Chancellor by January 1933, heading up a minority coalition with other conservative parties. The Nazis used the power of office in the hopes of electing a majority government. In preparation for the March 1933 election, the Brownshirts—the Nazi paramilitary wing—infiltrated the police, broke up other political party meetings, seized assets of opposition parties, and threatened or beat opponents. Meanwhile, businesspeople threw their support behind the Nazis due in part to a fear of rising Communist support.

Despite all this, Hitler only achieved a minority 43% of the vote in March. Not having the majority he desired, Hitler instead passed the Enabling Act. This law gave him dictatorial powers. It was passed with support from right-leaning parties, and by physically forcing Social Democrat and Communist members from the Reichstag. Once passed, the Reichstag was powerless. It only met 19 times and adopted seven laws. The Nazis’ 986 other laws were all simply proclaimed by the government. This included a law that banned all other political parties.

Nevertheless, Hitler still held elections in 1933, 1936, and 1938. However, the only choice on the ballot was the Nazis. Voters could either vote for or against them. In each election, Nazis received over 90% approval. While many Germans supported the one-party state because they had grown frustrated with the instability of liberal democracy, many others cast approving ballots out of fear.

Paul von Hindenburg, German president and constitutional head, 1925-1934. He signed into law Hitler’s Reichstag Fire Decree and his Enabling Act. When Hindenburg died, Hitler made himself president thus ending any constitutional checks on his power.