Menu

Menu

Menu

Menu

Official state satire from the Nazis failed by 1938. While the Nazis had their own explanation, so do propaganda experts.

There is no question that Nazi state satire was unsuccessful. Die Brennessel, the official Nazi satire magazine, ceased publication in 1938. Meanwhile, the independent (but Nazi-supporting) satire magazines Kladderadatsch and Simplicissimus carried on, though with waning circulation. While it is difficult to peg an exact reason of why state-created satire failed in Nazi Germany, there are several possibilities.

Die Brennessel claimed that it failed because it had accomplished its goals. The magazine wrote its own obituary in its penultimate issue:

It was our Brennessel that tens of thousands of National Socialist readers enjoyed during the period of struggle as it gave the sharp and hated blows that gradually wore down the old system.

It was Brennessel that after the seizure of power took sure aim at external enemies and the moaners and complainers at home.

It was Brennessel whose scorn inflicted deep wounds on the enemy, that made them the laughing stock of the world, that made them look ridiculous.

We thank our readers for their loyalty. They know how much Brennessel (a piece of history of our party) served the idea through sharp attack and resolute defense until its greater goal was realized, the goal of its entire struggle: the creation of the Greater German Reich!13

It is true that the magazine folded when the Nazis were at the height of their domestic popularity. However, like most any official Nazi statement, Brennessel’s words need to be taken with a grain of salt.

German communications history professor Patrick Merziger, along with Randall Bytwerk, believed that Die Brennessel failed largely because it was limited in what it could criticize. Even with the power of the state behind it, the magazine had surprising confines on what it could say.

The German public felt that their standing within the Nazi state was being jeopardized by the satire.

For example, Merziger found that whenever the Volksgemeinschaft—the racially unified German community idealized by the Nazis—were satirically criticised in Die Brennessel, Die Brennessel received many letters objecting to the portrayal. Merziger said the letters were rooted in a belief that “a laugh that attempted to exclude could not be tolerated because to be shut out of the Volksgemeinschaft meant total exclusion.”14 In other words, the German public felt that their standing within the Nazi state was being jeopardized by the satire.

Nazi satirists first responded by telling people to get a better sense of humour. However, they soon caved, and satirical portrayals of the Volksgemeinschaft ceased. Because the Nazi state was unwilling to engage in societal self-criticism by satirizing the Volksgemeinschaft, the only thing left for them to satirize was foreign nations and the people at home who complained about the Nazis.

What little Die Brennessel had left to satirize was still heavily censored. For example, Randall Bytwerk found instances of mild Italian jokes being pulled from the magazine by Nazi censors, due to the fact Italy was a German ally. Bytwerk believed that all these constraints left the magazine “with precious little room to criticize.” He said:

Humor is often a way of dealing with the stresses of everyday life, rendering them more endurable through laughter, but Brennessel permitted no such release. The complainers, the moaners, the dissatisfied, they were the magazine’s enemies, its frequent targets. It suggested that to criticize life’s difficulties was to be a traitor.15

In the end, an all-controlling state such as Nazi Germany—with its blindered quest to create a single-thinking nation with little room for critical thought—ultimately could not engage in self-reflection through satirical criticism.

Given the Nazi drive to create a single-thinking society, it comes as little surprise that in satire’s place came uncritical comedy and farce. The share of comedy in Nazi Germany’s theatre programmes rose from 26 percent in 1933 to 38 percent in 1935 to 68 percent in 1941, a growth “representative of the trend in all other forms of media.”16 The replacement of satire with uncritical humour would be just what a monotonizing, top-down state like Nazi Germany would want: entertainment that functioned as a distraction from political reality.

13. Bytwerk, Bending Spines, 126.

14. Merziger, “Humour in Nazi Germany: Resistance and Propaganda?” 289.

15. Bytwerk, Bending Spines, 127.

16. Merziger, “Humour in Nazi Germany: Resistance and Propaganda?” 281.

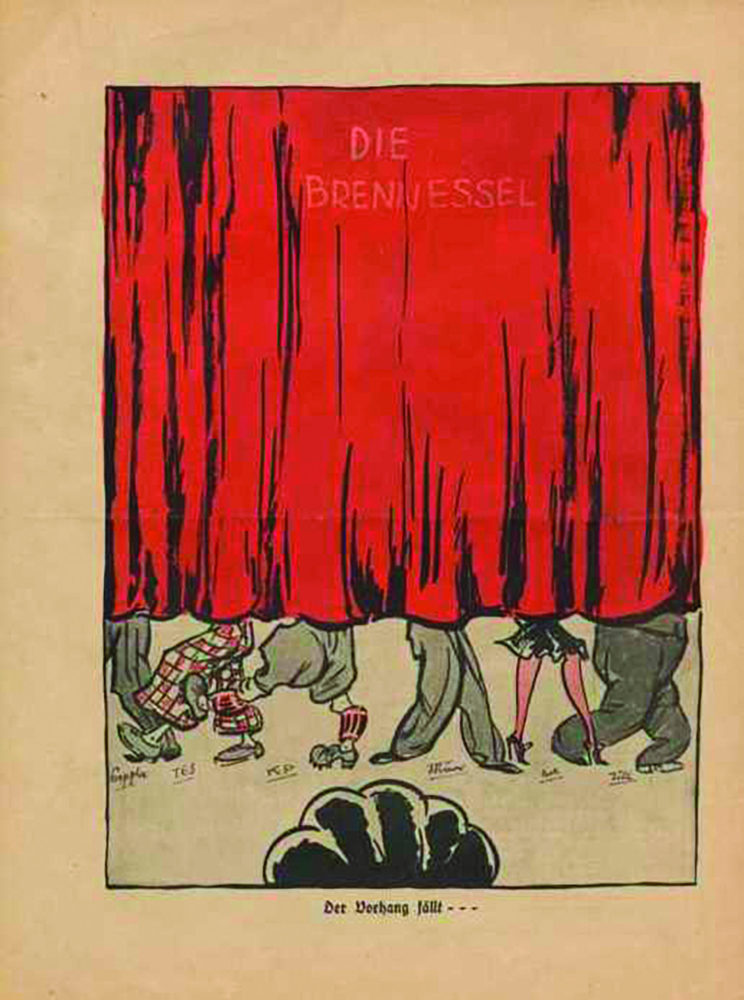

The back cover of the final issue of Brennessel, December 1938. The initials are those of the magazine’s most prominent cartoonists.

17. Elliott, The Power of Satire.

Historian Ian Kershaw has pointed out that the Nazis reached the peak of their domestic popularity in 1938. This was the result of a series of foreign policy successes for Hitler and a general rebuilding of the German economy. However, it is difficult to gauge the level of genuine German buy-in to the Nazi regime.

It is safe to assume that the over 90% support that the Nazis received in their three elections cannot be considered accurate. But the absence of independent public opinion surveys—alongside the lack of a public political alternative—makes gauging the actual level of Nazi popularity difficult.

Further complicating understanding people’s beliefs in Nazi Germany is the reality of a state like Nazi Germany. Historian Donald L. Miller has pointed out that “in a police state, withdrawing support for the government means death.”18 And historian Jörg Friedrich has pointed out that “civilian populations have a special war aim, which is completely different from their leaders’ war aims. It is a very simple one. The war aim of the civilian population is to survive.”19 Such factors would make people more inclined to pretend they supported the government.

While there is no question that there were Germans who supported the Nazi regime, understanding the exact level of support may ultimately be an impossible task.

18, 19. The Bombing of Germany, produced by Mark Samels (2010; Boston: WGBH Educational Foundation).